Understanding the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) in public health research

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) is a widely used measure in public health research and policymaking relating to health inequalities. By identifying areas with the greatest levels of deprivation, resources can be allocated more effectively to tackle systemic issues that contribute to unequal health outcomes. This blog provides an overview of the IMD and it’s use in public health research.

How it’s calculated

The IMD is a measure of relative deprivation* in England, produced by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). The index was last update in 2019, and the next release is expected to be in late 2025. It is a composite measure that takes into account 39 indicators across seven weighted domains of deprivation:

- Income (22.5%)

- Employment (22.5%)

- Health Deprivation and Disability (13.5%)

- Education, Skills, and Training (13.5%)

- Crime (9.3%)

- Barriers to Housing and Services (9.3%)

- Living Environment (9.3%)

While the original IMD scores are calculated at the Lower Layer Super Output Area (LSOA) level – containing about 1,500 residents – the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) adapts them for use at the general practice level. This is done by taking a population-weighted average of the IMD scores for all LSOAs where a practice’s registered patients live. This ensures a more accurate reflection of deprivation experienced by the population served by a practice.

How IMD relates to health inequalities

IMD is used to measure the relative socioeconomic status of different areas in England. Researchers often stratify areas into quintiles based on relative deprivation in order to examine systemic differences in health care, such as funding, workforce distribution, life expectancy, or rates of chronic disease.

Research consistently reveals “inverse care” effects, whereby more deprived areas with greater need often have fewer or less accessible services: in 2023, practices serving the most deprived patients in England received £16.20 less funding per weighted patient than those serving the least deprived. Furthermore, studies have shown that individuals living in the most deprived quintile experience significantly higher rates of chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mental health disorders compared to those in the least deprived quintile.

Difference between area- and patient-level effects

IMD is useful for comparing deprivation between neighbourhoods, at the area-level. However, many analysts and researchers make the mistake – known as ecological fallacy – of applying the neighbourhood IMD score to individual residents living in a neighbourhood, at the patient-level.

We know that the effects of neighbourhood socioeconomic status on health outcomes are independent from the impact of the household or individual socioeconomic status. For example, an affluent person living in a deprived neighbourhood, according to the IMD, may experience disadvantage because of their neighbourhood conditions, such as lack of green space. Nonetheless, their own economic circumstances may buffer them from this impact and enable them to create health promoting conditions for themselves and their household. This is particularly true for highly urban or rural areas, where there can be a big difference in the socioeconomic position of residents within neighbourhoods. As such, the IMD should be applied to area-level analysis, as opposed to patient-level.

Introducing a Complete IMD Dataset

Fingertips, a platform maintained by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), provides practice-level IMD scores. However, the publicly accessible data only includes active general practices, limiting its utility for historical or longitudinal studies. To address this, HEEC team obtained a supplementary data file directly from OHID containing IMD scores for closed practices that were active in earlier years.

Handling sparse time points

IMD scores are only available for 2010, 2015, and 2019. These gaps make it challenging to analyse trends across time or conduct longitudinal studies effectively. We overcame this limitation using:

- Interpolation: We used linear interpolation to estimate IMD scores for years between the available time points (e.g., 2011-2014, 2016-2018).

- Extrapolation: For years beyond the most recent data point (2020-2024), we extrapolated scores based on the trends observed in the available data.

Creating a complete dataset

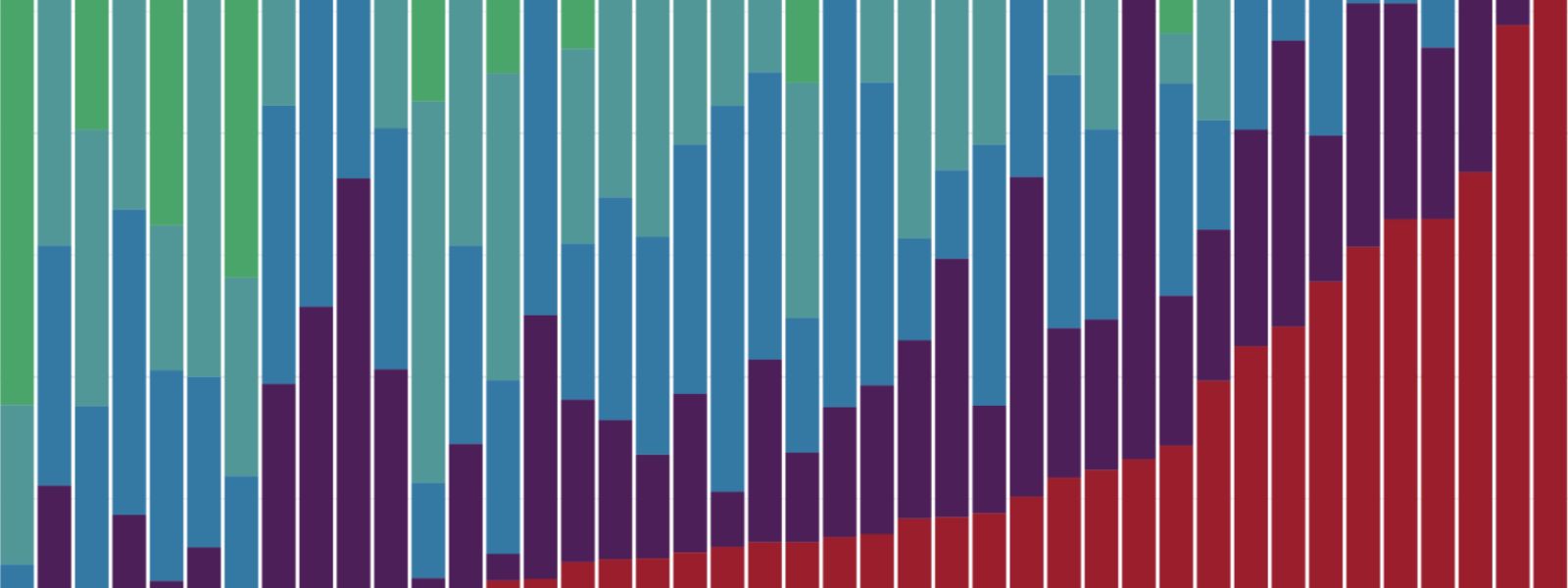

To enhance usability, we stratified practices into IMD quintiles for each year, where quintile 1 is the least deprived and quintile 5 the most deprived. This can be done at both the Integrated Care Board (ICB) and national levels:

- National quintiles: These quintiles compare practices across all of England. They provide a more representative view of relative deprivation across the country, which is particularly useful for nationwide studies or comparisons.

- ICB quintiles: These rank practices within a specific region or ICB. While useful for identifying the most and least deprived practices within an area, they may not accurately reflect deprivation compared to national standards and can suffer from small sample sizes.

For our analyses, national quintiles are preferred, but local quintiles may be useful for region-specific analyses or localised decision making. Our work resulted in a complete time series of practice-level IMD scores, covering all practices ever included in the data. The final dataset can be downloaded here:

Download IMD_interpolated.csv.

How to measure health inequality using IMD

The IMD dataset becomes especially powerful when merged with other practice-level health or health care indicator datasets, such as chronic disease prevalence or patient satisfaction scores, using the NHS practice code as the key. For example, in order to measure socioeconomic inequalities in the general practice workforce, we obtained GP workforce data from NHS Digital (available here) and merged it with the IMD data. This revealed stark disparities in workforce distribution, with practices in the most deprived quintile having 7.5 fewer full-time equivalent (FTE) GPs per 100,000 patients compared to those in the least deprived quintile.

This approach allows for detailed analyses of how deprivation impacts various aspects of health care, including workforce distribution, funding allocations, and patient outcomes.

Conclusion

The Index of Multiple Deprivation is an invaluable measure for understanding and addressing health inequalities in England. While its limitations, such as sparse time points and omission of closed practices, present challenges, these can be mitigated through interpolation, supplementary data, and careful merging with other datasets. By leveraging IMD in conjunction with health indicators, we can gain deeper insights into the drivers of inequality.

* The perception by an individual that the amount of a desired resource (e.g., money, social status) they have is less than some comparison standard. This standard can be the amount that was expected or the amount possessed by others with whom the person compares themself.