How to screen for social needs in primary care

This how-to guide aims to provide a practical guide to social needs screening in primary care by: summarising existing knowledge, opportunities and challenges; describing a step-by-step guide to implementation for integrated care boards, primary care networks and practices; and highlighting strategies to support design and implementation.

How-to: Screen for social needs in primary care[PDF 146kb]

Download documentSummary

There is an opportunity in primary care to collect information on and support patients in their social needs. This step-by-step guide aims to provide guidance for implementing social needs screening. Although this is relatively new in the UK, there is a large body of evidence supporting the substantial potential benefits of screening including improving patient quality of life, reducing disparity in health and care outcomes, gathering more precise information on populations, and targeting services to support the most disadvantaged.

What are social determinants of health and what is social needs screening?

Social determinants of health (SDoH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live and age, and the broader societal, economic and political forces and systems that shape this. Unequal distribution of SDoH drives health inequalities and is fundamental in shaping health outcomes; examples include income, education, employment, housing, violence or conflict and discrimination (1).

Social needs screening is a systematic and purposeful collection of information about an individual’s social circumstances and supports action on health inequalities through addressing the unequal distribution of the SDoH.

Social needs screening involves healthcare staff using a screening questionnaire to ask patients about SDoH such as financial difficulty, housing and transport. Patients who want help are offered referral to support, such as link workers or social prescribers, who can direct them to appropriate support.

Why consider social needs screening?

Primary care is situated at the frontline of managing the negative impacts of social problems. A pre-pandemic survey of General Practitioners in the UK found that approximately 1 in 5 appointments were for issues relating predominantly to social needs, costing £400 million per year (2). This is likely to be much higher in areas with high levels of poverty and social need.

Social needs screening can improve patients’ health and wellbeing. Research shows that social needs screening can:

- Identify people requiring additional social support (3)

- Predict future health outcomes (4)

- Reduce social problems (5)

- Improve health outcomes such as child health, smoking cessation, depression, blood pressure and lipid control (5)

- Improve adherence to treatment regimens and increase immunisation rates (5)

- Reduce A&E attendance and hospital readmissions (5)

- Improve quality of consultations by enhancing a personalised care approach (6)

Targeting services and resources to address inequalities in SDoH requires a good understanding of the problem, based on robust data. Currently most population health management approaches use area-level measures of deprivation, such as the Index of Multiple Deprivation. While these are useful at understanding neighbourhoods, they are inaccurate at identifying individual disadvantage and underestimate individual poverty (7). Systematically collecting individual-level social needs data can provide more accurate patient-level data to leverage resources and target services more effectively.

Potential challenges

General practice is overstretched. Long-term success requires multi-disciplinary engagement and embedding into existing workflows, rather than relying on GPs asking questions during consultations. This could be through administrative staff, social prescribers or social workers collecting information, or using innovative tools such as self-administered online or text forms.

Community services are overstretched. It is essential that there is support for patients who report a social problem and want onward referral. Raising expectations without offering further assistance risks losing patient trust as well as being ineffective.

While most studies have found screening to be acceptable to patients (8), it is important to bear in mind that questions may be unexpected or feel intrusive to some patients and to acknowledge this in the design of a programme.

There are challenges in terms of using the social data that could occur if practices, PCNs or ICBs are collecting different information. Having regional or even national consensus of the questions and SNOMED codes will be important in optimising the use of the data in research and planning. Working at a larger scale will also minimise duplication of work.

Steps to undertaking social needs screening

Step 1: Develop a multi-disciplinary leadership group. This may include clinical leads, practice managers, social prescribers, patients and local voluntary and community and social enterprises (VCSE). Collecting social information from patients requires technical support to code information, operational planning focused on how to collect the information and strategic collaboration with VCSE to support those who want help.

Step 2: Map community resources. It is important to map community resources with local government and VCSE organisations. This may build on existing social prescriber expertise; however, involvement of patients, VCSEs and the wider team is likely to identify more community assets.

Step 3: Decide which screening questions to ask. Many versions of screening tools exist; from a single question to extensive questionnaires (see strategies below). There are advantages to having local, or even national agreement on the information being collected to develop consistent data.

Step 4: Develop a patient pathway. Each pathway will be different. Using existing systems and structures will minimise additional burden of work. Considerations include:

- if screening is across the entire practice population, or if it is targeted to at-risk groups, or if it is opportunistic, for example, at registrations, during consultations or long-term condition reviews,

- staff members asking the questions,

- how questions are asked, for example by text, phone or face to face,

- the referral pathway for patients who want further support,

- the process for re-screening and keeping data current, including how often and which questions to ask.

Step 5: Create supporting electronic health record codes and templates. Integrating questions into existing templates, for example for annual reviews, social prescribing assessments and registrations will streamline the workload and facilitate data extraction. Some codes exist for social data which may be easier to use rather than create new ones. Consider what data will be needed for monitoring and evaluation. For example, it may be useful to have a code for different referral options.

Step 6: Staff training. Ensure staff understand the importance of the SDoH and the impact they have on the health service. Provide practical training for the programme, including how to ask SDoH questions, the patient pathway, how to refer patients and how to accurately record the information in the electronic health record.

Step 7: Monitoring and evaluation. As with any new service, monitoring and evaluation is important to ensure successful implementation.

Strategies to consider

Work with other Integrated Care Boards or Primary Care Networks

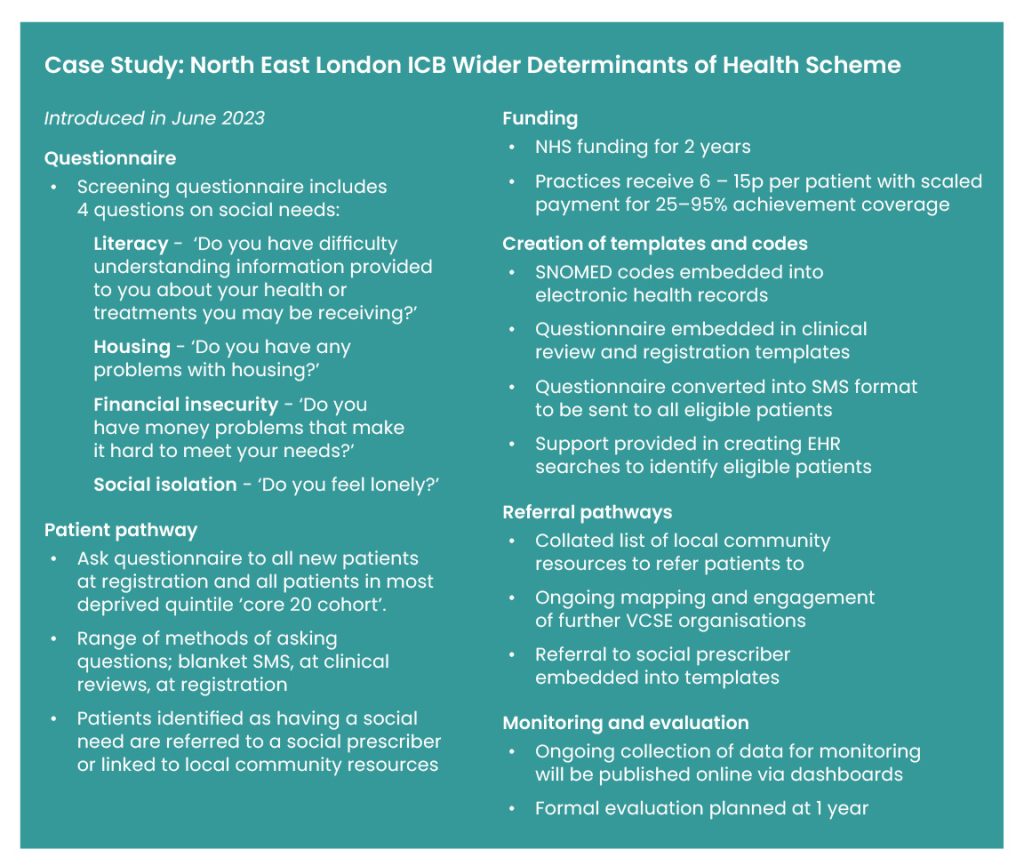

While aspects of implementation may vary from place to place, the key to success is collaboration. Working at a regional or national level will reduce workload for individual practices and consistent data recording across practices will optimise the potential of social needs screening to support population research, planning, and multi-site evaluation. Collaboration between ICBs and PCNs for support on implementation, and to share SNOMED codes and templates, will avoid duplication. Drawing learning from other parts of the country that have already successfully implemented social needs screening is important (for example see case study).

Consider funding

ICBs or PCNs may be able to introduce social needs screening using existing budgets while others will require additional funding. North East London ICB has funded a service where practices receive per patient payments for achieving agreed levels of screening coverage (see case study) (9).

Collaborate early with community services

Engage with community resources early to understand their eligibility, capacity, and referral pathways. This includes working with them to manage capacity and demand where necessary.

Use or adapt existing screening tools

The Social Interventions and Research Evaluation Network (SIREN) lists many social needs screening tools used in North America (10). These vary considerably and most are not validated. While some tools ask more than 30 questions, other examples ask only one screening question to prompt a more thorough assessment. Collaborate regionally to agree on which tools are used; examples from existing schemes can be used (see case study).

Collaborate with patients

Co-designing a programme with patients increases the likelihood of meaningful, acceptable, and effective change.

Case Study: North East London ICB Wider Determinants of Health Scheme

References

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health, in Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report. 2008, World Health Organisation. Available from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1

- Citizens Advice, A very general practice: How much time do GPs spend on issues other than health., in Citizens Advice policy briefings. 2015. Available from https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Public%20services%20publications/CitizensAdvice_AVeryGeneralPractice_May2015.pdf

- Brcic, V., C. Eberdt, and J. Kaczorowski, Development of a tool to identify poverty in a family practice setting: a pilot Int J Family Med, 2011. 2011: p. 812182.

- Singh-Manoux, A., M.G. Marmot, and N.E. Adler, Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med, 2005. 67(6): p. 855-61.

- Yan, A.F., et al., Effectiveness of Social Needs Screening and Interventions in Clinical Settings on Utilization, Cost, and Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Health Equity, 2022. 6(1): p. 454-475.

- Tong, S.T., et al., Clinician Experiences with Screening for Social Needs in Primary Care. J Am Board Fam Med, 2018. 31(3): p. 351-363.

- Pardo-Crespo, M.R., et al., Comparison of individual-level versus area-level socioeconomic measures in assessing health outcomes of children in Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2013. 67(4): p. 305-10.

- Caicedo, N.M.A., et al., Integration of social determinants of health information within the primary care electronic health record: a systematic review of patient perspectives and experiences. BJGP Open, 2023: p. BJGPO.2023.0155.

- Clinical Effectiveness Group. Data Accreditation and Improvement Incentive Scheme. 2023; Available from: https://www.qmul.ac.uk/ceg/support-for-gp-practices/resources/gp-contract-guidance/daaiis/.

- Social Interventions Research & evaluation Network. Social Needs Screening Tool Comparison Table 2019 11.08.2023; Available from: https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/tools-resources/resources/screening-tools-comparison.

Suggested citation

Painter H, Dehn Lunn A, Parry E, Gopal D, Marszalek M, Ford J. How-to guide: How to screen for social needs in primary care. Health Equity Evidence Centre; 2024.