Inequalities in Continuous Glucose Monitoring for young people with diabetes

In recent years, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) has become an increasingly important part of diabetes care. This implantable technology uses disposable sensors to transmit up-to-date blood glucose data to a connected smartphone, preventing the need for repeated finger prick testing. By reducing the pain and effort associated with repeated blood sugar sampling, CGM is transformative for young patients and has been shown to lead to better blood sugar control. However it comes at a cost – between £80-140 per month. Despite this, many countries are now moving to partly or completely fund CGM, especially for children with type 1 diabetes (T1D).

For several years there have been growing concerns that there has been lower uptake of CGM amongst disadvantaged groups, including children from minority ethnicities and more socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. Access inequalities may be compounded by suggestions that, even amongst young people using CGM, more advantaged groups may derive disproportionate benefit. To obtain maximum benefit from CGM, users must regularly check their blood sugars and adjust their insulin dose accordingly. This sort of ‘high agency’ intervention, which takes more effort from children and parents, has previously been shown to lead to an increase in inequalities.

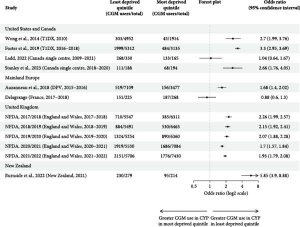

We undertook a systematic review to explore inequalities in CGM for young people with T1D. We found consistent associations between lower CGM use and minority ethnicity (particularly for black children), those living in more socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, lack of private insurance, and lower parental education. Inequalities were particularly stark in New Zealand and the USA, where public funding for CGM is limited or non-existent, which suggests that the high cost of CGM is likely an obvious but important factor in CGM inequalities.

However, clear disparities were evident even in the UK, where CGM was fully funded for children meeting certain criteria. At the time of our systematic review, NICE recommended CGM should be offered to all children with high risk or frequent episodes of hypoglycaemia, and suggested considering offering CGM to children who were either under school age or had poorly controlled diabetes. There is no strong evidence that children from ethnic minority communities or lower socio-economic areas have a lower risk of hypoglycaemia. There is however a significant volume of evidence suggesting these groups tend to have higher average blood sugars. As a result, these guidelines would be expected to generate inequalities in the opposite direction to those we see in the data. A number of mechanisms have been explored that may have contributed to the observed disparity in CGM use for disadvantaged groups, including both reduced acceptability, for example due to factors such as stigma and higher levels of alarm fatigue, as well as implicit bias amongst prescribers and lack of adherence to guidelines.

In 2023, shortly after the end of this systematic review’s study period, there was a change in guidelines in the UK in which eligibility criteria were substantially broadened with CGMs being recommended for all children and young people. Since then, there has been remarkable uptake in CGM for all groups and inequalities have narrowed significantly, with all groups achieving over 90% CGM use. It may therefore be that removing guidelines, particularly those that leave decisions open to clinician discretion, is a powerful tool to reduce inequalities.

Finding effective ways to address these access inequalities is particularly important as our research also found evidence that, despite concerns that CGM relies on ‘high agency’ for maximum benefit, this technology appears to have similar benefits for all groups, irrespective of ethnicity or socioeconomic status. However, these concerns cannot be entirely dismissed as the evidence was somewhat limited and one study found that lower parental education may be associated with less benefit from CGM.

One technology that may sidestep this potential source of inequality is the ‘artificial pancreas’, or hybrid closed-loop system, which allows the CGM sensor to ‘talk’ directly to the insulin pump, removing the need for the user to manually calculate and adjust insulin doses based on CGM readings. Though it is more costly, this technology has been associated with even better outcomes than CGM alone, and has subsequently been recommended by NICE for all children <18 with T1D. Since rollout commenced in April 2024, preliminary data suggests inequalities have started to significantly erode in access to hybrid closed loop too.

Removing cost and guideline barriers is a clear route to decreasing inequalities in access to diabetes technology. However, we have not yet seen narrowing of outcome inequalities of the same magnitude as improvements in technology inequalities, as we might have hoped. This is in keeping with previous studies that have suggested adjusting for observed inequalities in access to technology reduced but did not eliminate inequalities in HbA1c. There is clearly still some way to go for equitable diabetes care.