Health inequity is built into policy, not into people

Health inequity is not the product of individual behaviour, but of policy design. Drawing on a comprehensive synthesis of recent evidence, this blog examines why public policies that reshape social and material conditions are more likely to reduce health inequities than those that rely heavily on individual agency, and how a policy-focused framework can help anticipate these effects.

Health inequity remains one of the most persistent and consequential failures of high-income countries. Across Europe and North America, populations living in socioeconomic deprivation experience substantially shorter life expectancy and higher burdens of morbidity than their more affluent counterparts; often by margins of seven to ten years. These discrepancies are neither stochastic nor biologically determined. They are systematic, avoidable, and socially produced: shaped by housing, income, education, employment, and access to public services.

Yet, contemporary public health policy has increasingly gravitated towards interventions framed around individual behaviour: stop smoking, eat better, be more physically active, manage personal risk. Such prescriptions are not intrinsically incorrect; however, they implicitly assume levels of stability, time and psychological capacity that are unevenly distributed across social groups. The critical question, therefore, is not whether interventions improve population health in aggregate; but whether they reduce health inequity between socioeconomic groups.

Our recent umbrella review represents the most comprehensive synthesis to date of population-level policies shown to reduce health inequity in high-income countries. In doing so, it introduces a novel conceptual framework for organising, interpreting and comparing the equity consequences of public policy interventions.

A framework that reorders the problem

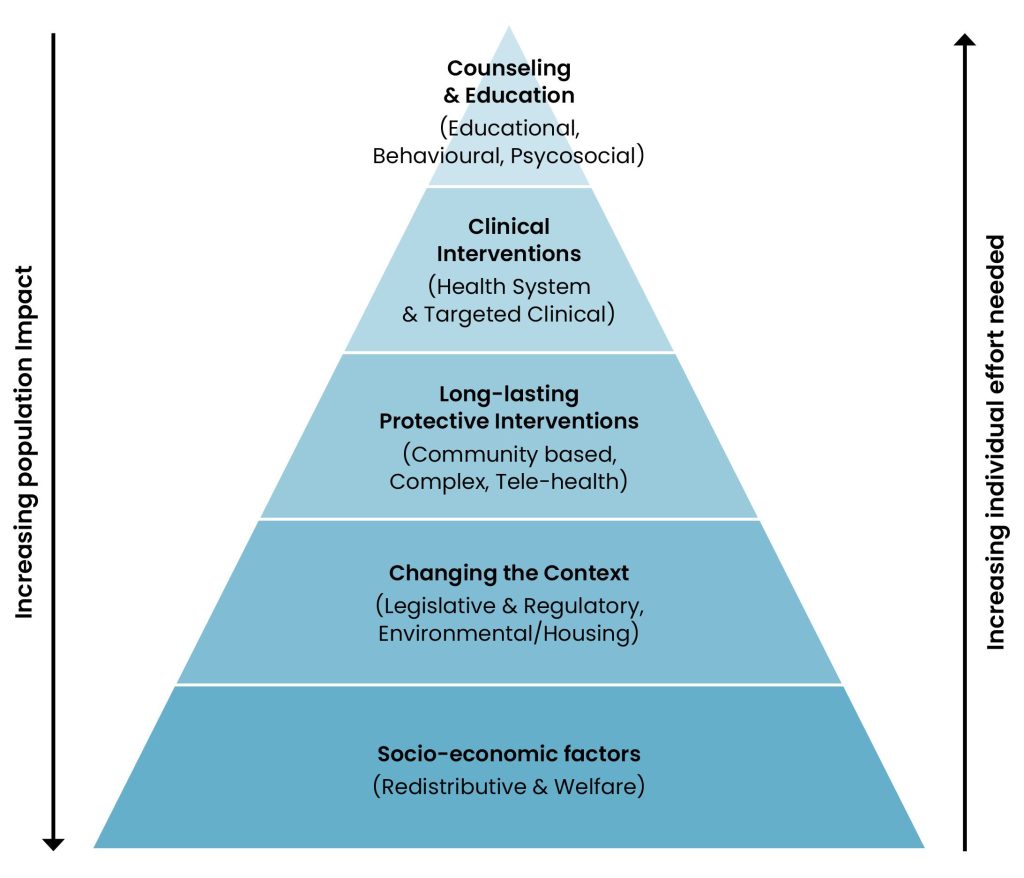

To synthesise a heterogeneous and methodologically diverse literature, we developed a conceptual framework termed the Health Equity Pyramid. This model orders public health interventions according to two interrelated dimensions: the degree of individual agency required for benefit versus the scale of population reach.

At the base of the pyramid are interventions that reshape the social and material environment, including redistributive welfare policies, housing provision and legislative or regulatory measures. These interventions require minimal active decision-making from individuals, termed ‘agentic demand’, and exert effects across large population groups. Ascending the pyramid are interventions that increasingly depend upon sustained agentic demand, motivation and engagement, such as educational programmes, digital health tools and self-management interventions.

This distinction is not merely classificatory. Individual agency is itself socially patterned. Cognitive resources, financial security and time availability are unequally distributed across society. An intervention that appears neutral in design may therefore produce systematically unequal effects in practice.

By applying this framework across 35 systematic reviews published since 2017, we were able to compare intervention types not only in terms of effectiveness, but in relation to their capacity to reduce or exacerbate health inequity.

What works best: changing conditions, not only choices

The most consistent and robust reductions in health inequity were evidenced in interventions located at the lower levels of the pyramid. Income support, food subsidy schemes and welfare reforms improved food security, reduced financial strain and were associated with improved maternal and child health outcomes. Housing interventions stabilised living conditions, improved mental health and reduced emergency hospital utilisation among people experiencing homelessness. Legislative measures, such as smoke-free policies and reforms to prescription drug costs, reduced harmful exposure and improved access to treatment at population scale.

These interventions share a defining characteristic: they alter the structural conditions in which health is produced. Rather than requiring individuals to overcome socioeconomic barriers through sustained effort, they modify or remove those barriers directly. In doing so, they reduce the cognitive and material burden required to achieve health gains.

This finding reinforces a long-standing but frequently marginalised principle of public health: durable reductions in inequity are more likely when interventions reshape social context rather than attempt to compensate for disadvantage through information or exhortation alone.

When behaviour-focused interventions help, and when they harm

Interventions higher up the pyramid produced more variable and contingent results. Educational, behavioural and digital interventions were capable of reducing health inequity when explicitly designed for disadvantaged populations: ‘culturally tailored’. Tailored smoking cessation services delivered through primary care improved quit rates among low-income groups. Hospital discharge coordination for people experiencing homelessness reduced readmissions and improved continuity of care. These examples demonstrate that clinical and behavioural interventions can contribute to equity when embedded within supportive institutional structures.

However, when such interventions were implemented without contextual adaptation, a contrasting pattern emerged. More advantaged groups were more likely to participate, persist and benefit. In several instances, overall health outcomes improved while health inequity widened.

This phenomenon, termed ‘intervention-generated inequity’, arises when a policy relies heavily on individual agency within a socially stratified population. It reflects not flawed intention but flawed assumption: that knowledge translates uniformly into action, and that the capacity to act is evenly distributed. Under conditions of structural inequality, information itself becomes an axis of inequity.

Why the framework matters beyond this review

The Health Equity Pyramid offers more than a descriptive taxonomy. It provides a conceptual framework through which to anticipate the equity consequences of policy design. It reframes equity as a question of burden allocation: who must act, how often, and under what constraints.

Within the broader landscape of public health strategy, this has important implications. It suggests that innovation alone will not resolve health inequity if it increases the demands placed on populations with the fewest resources. It also provides a practical heuristic for policymakers to evaluate distributive effects prospectively, rather than identifying unintended harms retrospectively.

Most importantly, it clarifies that equity is not an incidental by-product of effective policy. It is an intrinsic property of policy design.

Implications for policy and practice

If reducing health inequity is a substantive objective, then public policy must prioritise interventions situated at the lower levels of the pyramid: income security, housing stability and regulatory protection. These should constitute the foundation of equity-oriented strategies, with higher-agency interventions deployed selectively and designed around the lived realities of disadvantaged populations.

Health systems can contribute when services are targeted, coordinated and accessible. Behavioural interventions should reduce cognitive burden rather than amplify it. Digital tools should complement, not substitute for, structural support.

Evaluation frameworks must also evolve. Policies should be assessed not solely on average effectiveness, but on distributive impact. Without stratification by socioeconomic position, apparent success may conceal widening inequities.

Conclusion

Health inequity is not, in its essence, a failure of individual behaviour. It is the cumulative and foreseeable consequence of how societies allocate risk, security and opportunity across populations. Our review demonstrates that policies characterised by minimal individual agency and maximal population reach yield the most consistent and durable equity gains. Interventions that rely heavily on personal action may confer benefit, but only when deliberately designed to accommodate structural disadvantage; when they are not, they risk entrenching the very inequities they purport to remedy.

If public health is genuinely committed to narrowing the gap, it must move beyond the moral language of instruction and exhortation and instead invest in reshaping the social and material conditions under which health becomes possible.